A new Iwata Asks interview delves deep into Nintendo history and chronicles the design and production of the Game & Watch handheld game systems.

As you have probably seen via Super Smash Bros. Melee and Brawl, which revived the “mascot” character (now known as “Mr. Game & Watch”), the game systems each had a self-contained game to play in the during the 80’s, with game’s like Octopus, Fire and Chef. Although theses were all single-screen affairs, the systems eventually evolved into dual-screen devices which ended being the precursor and inspiration to the design Nintendo would use with the DS (dual-screened clamshell design).

In modern times, various games from the Game & Watch series have been compiled into Game Boy and Game Boy Advance compilations, as you can read about in my Game & Watch Gallery review. You can also purchase Game & Watch Collection 1 and 2 for the DS via Club Nintendo. You must get them by earning enough coins by registering Nintendo products. Of course, you can always find them on ebay as well.

Although fan-translated, here is the first few parts of the Iwata Asks interviews, which shed some interesting light on the early days of Nintendo.

Part 1 – The Era When Developers Could Do Anything

Iwata: Hello.

All: Hello.

Iwata: This time, in a first for me on “Iwata Asks,” everyone in the group I’ll be talking to has more experience than I do, both in life and at Nintendo. The gentlemen I’ve asked here today led the design of Nintendo’s first portable gaming system, the Game and Watch, which was the ancestor of both the Game Boy and the Nintendo DS. Thank you for kindly agreeing to the request, everyone.

All: Thank you for the invitation.

Iwata: To begin, I’d like to ask you all to talk about what were your roles were in the company during the development of the Game and Watch. Let’s begin with Mr. Kano.

Kano: It was such a long time ago, some of my memories are a little fuzzy. Nintendo in that period had very few people that were responsible for design…

Iwata: As a matter of fact, I believe that when Nintendo began recruiting specialists in design, you were one of the first hired.

Kano: That’s right. When development on the Game & Watch began, I was assigned to a new department of the company called the “Creative Section.”

Iwata: That section had Mr. Miyamoto as a member as well, didn’t it? How many members were there, altogether?

Kano: Five, including myself. When it was decided to develop the Game & Watch, there was no one in place we could call a lead designer. Because of that, everyone had a hand in everything, from the design of the gameplay, to the design of the device, its colour, the packaging, etc. My role was to oversee all these aspects.

Iwata: So from the design of the “Mr Game & Watch” character himself, right down to the box the system came in, you were involved in all aspects of creating the Game & Watch.

Kano. Right. You could call me a “jack of all trades.” But it wasn’t just me, every employee had to be a jack of all trades back then.

Iwata: What were your responsibilities, Mr. Izushi?

Izushi: My area of responsibility was to develop the basic software that made the game run. I shared that job with Mr. Yamamoto.

Yamamoto: Mr. Izushi and I took turns developing the software. And as Mr. Izushi said, each of us was a “jack of all trades,” and so I also participated in meetings to think of new ideas for games. Everybody threw in their own ideas, and things were worked with lots of friendly back-and-forth.

Iwata: And in those days, the roles of software programming, planning, and hardware engineering weren’t as clearly differentiated as they are now.

Izushi: That’s right.

Iwata: So even people who were hired as hardware engineers also wrote software, contributed ideas, and sometimes even contributed art. (laughs)

Yamamoto: Yes. we did everything from make art to oversee the arrangements for mass production.

Izushi: Finally, we even went to see the shooting of the commercial.

Yamamoto: That’s right, the commercial. Once when I visited the set, all the staff said “good morning” to me, even though it was the afternoon. I thought it was a little strange.

Iwata: (laughs)

Izushi: As part of behind-the-scenes work on the commercial, we hid under a big box and played the game.

Iwata: You played the game hidden under a box? (laughs)

Izushi. That’s right. We placed the game, which was connected by a cable, under a big box. The sides of the box were brightly illuminated. We placed a Game & Watch inside, and took pictures of a friend posing as if he were playing the game. I remember spending so long under that box that the light blinded me when I finally came out.

Iwata: Aha, ha, ha! (laughs)

Izushi: Still, it was all a valuable experience.

Yamamoto: A truly valuable experience.

Iwata: I’ll never forget the ad for the “Multiscreen” system.

Izushi & Yamamoto (singing in unison) “Multi, la la la, multi.”

Iwata. That’s right, that’s right! (laughs)

Izushi. I remember the tune because I spent so much time listening to it, sitting in that box.

All: (laugh)

Iwata: Next question. What year did you all join the company?

Kano: I joined the company earliest, in 1972. Nintendo at that time only had one section dedicated to product development, and soon after I joined, I was assigned to the so-called “Development Department.”

Iwata: At that time, how many people, in total, were in development?

Kano: I think it was about 20…? The department was in charge of board games and mini-games.

Iwata: Back in 1972, the design of board games was definitely not high-tech, was it? Mr. Izushi, when did you join the company?

Izushi. I joined in 1975. I was also initially assigned to the Development Department, where I made targets for the “Custom Light Gun.” The targets were shaped like figures, and if you hit them, they would fall down. Mr. Kano was the one who designed the figures.

Kano: Those were the “Gunman” and “Lion” figures.

Izushi: I did all the work designing the mechanical movement, the chassis, and the packaging. I also gave a few ideas on how to make the whole thing more fun. I really did anything back then. After that, we started to make games for television sets, the type that didn’t have interchangeable software.

Iwata: “TV game 6” and “TV game 15,” right?

Izushi: Yes. I also planned and built the “Racing 112” and “Block Breaker” games that were launched later.

Iwata: How many years after Mr Izushi did you join the company, Mr. Yamamoto?

Yamamoto: I joined in 1978, so three years after Mr. Izushi. After joining and finishing the new hire training, I was assigned to the manufacturing section at the factory in Uji. There, I helped in the manufacture of arcade games, and the next year, I was assigned to the second section of the Development Department.

Iwata: When you joined, development had been split into two sections.

Yamamoto: That’s right. When I was assigned there, development of “Block Breaker” had ended and the talk had turned to what we should do next. I made protoypes for new games. We were on the verge of introducing the LSI, and I produced the necessary mask patterns by hand.

Iwata: At that time, game consoles didn’t use computers, and didn’t have programs written for them. Instead, you played with the hardware itself.

Yamamoto: Because computers weren’t common back, then, no.

Izushi: At that time the games were made by the hardware makers.

Iwata: New hardware was made for each game.

Izushi: So if the hardware maker wanted to make an adjustment, say make the game faster, he brought over a soldering iron and made changes to the wiring. That was something everyone had fun doing together, saying “hmm… maybe a little faster” and so on, making little adjustments, changing them again, and finally everyone said “this is it!” and we started mass production.

Part 2 – An Unmodified Calculator CPU

Iwata: So, you were all involved with the job of making the first Game & Watch, “Ball,” which launched in 1980.

Kano: Yes.

Iwata:Without changing the subject too much, HAL Laboratories was also founded in 1980.

Yamamoto: That makes exactly thirty years ago, then.

Iwata: Right. We have to face that the year is 2010, which means it was thirty years ago.

Yamamoto: We were all in our twenties back then.

Iwata: I was still in university. (laughs)

Izushi: Oh, yeah! (laughs)

Iwata: Yes. As a matter of fact, 1978, the year Mr. Yamamoto joined the company, was the year I entered university, and the year “Space Invaders” was such a huge hit.

Yamamoto. Is that right?

Iwata: And the year Mr. Izushi joined the company, 1975, is the year I entered high school. 1972, the year Mr. Kano joined, was the year of the Sapporo Olympics. I was in grade school at the time, living in Sapporo.

Kano: Oh! That’s really something. (laughs)

Iwata: As I sit here among the ranks of such great men as yourselves, I feel that some mysterious force must have compelled you to join together and make a product called “Game & Watch.”

By the way, this is something I heard second-hand, but apparently the birth of the idea that became the Game & Watch came when Mr. Yokoi (Gunpei Yokoi) was riding the bullet train and, by chance, saw a man playing around with his calculator. Did you ever hear anything from Mr. Yokoi about how he came up with the idea for Game & Watch?

Kano: No, unfortunately I don’t know that many details about it. When I was transferred from the Creative Section to the Development Section, development of the first Game & Watch title, “Ball,” was already underway. At that point, Mr. Yokoi and Mr. Okada (Satoshi Okada) had already built the prototype…

Iwata: You joined halfway through, so you aren’t acquainted with all the details?

Kano. No. But I have heard Mr Yokoi took his inspiration from pocket calculators.

Izushi: Don’t forget that the chip used in the Game & Watch was the same chip used in those pocket calculators. Originally, each number on the display of a calculator had seven segments…

Iwata: The numbers from 0 to 9 were displayed using a structure segmented into seven pieces.

Izushi: That’s right. Therefore, a calculator capable of calculating to eight places had eight rows of seven segments, for a total of 56 segments. Also, there were a few extra segments for mathematical symbols like the minus sign (-). The chip we used to make “Ball” could control a total of 72 segments.

Iwata: So in short, rather than use those 72 segments, which could each be turned on and off, to display numbers, you used them to display pictures, and used those to create a game.

Izushi: That’s exactly right.

Kano: Don’t forget that Ball’s screen has a counter in the upper right corner used to display the score or the time. That by itself used four columns of seven segments, or 28 segments.

Iwata: So out of a total of 72 segments, that left you 44.

Kano. Yes. The images of the character and the balls were created out of those remaining segments.

Iwata: I see. I’ve also heard that the idea to use the four-column point counter to also display the time came late in development.

Kano. As I joined development part way through, I don’t know the details of how the clock function was added, but considering that digital clocks usually have a colon in between the hours and the minutes, which the Game & Watch is missing, I can believe that the clock was an afterthought.

Izushi: A quartz crystal is an easy thing to add late in development, too.

Kano: Remember that adding a colon would have used up one of the segments. I’m sure they wanted to save that segment.

Iwata. It would have been a shame to use it up on something not game-related.

Kano: Yes, what a waste! (laughs) To address that, the second game, “Flagman,” could only display the digit “1” in the thousands column, and only by the sixth game, “Manhole,” was there a display for “AM” and “PM.”

Iwata: Why could it only display the digit “1”?

Kano: Well, for example, to display “10:00 PM,” you need display “AM” and “PM,” as well as four rows, which use 28 segments.

Iwata: Right.

Kano: If you make it so the thousands column can only display the digit “1”…

Iwata: I see. “AM,” PM,” and “1” together make three segments, but to display a full digit, you need seven segments, so that way you can save four segments. (laughs)

Kano. It’s a significant savings. We wanted to even just four extra segments for gameplay, if we could get them. It did mean that the highest possible score was 1999, though.

Iwata: Aha ha ha! (laughs)

Izushi: With tricks like that we could reduce the number of segments used, and use them elsewhere.

Kano: Not even a single segment was wasted.

Izushi: And to fit within those restrictions, we had to think up all kinds of ideas. It was very fun to think of ways of making games with just a few available building blocks.

Kano: Exactly, that was the most interesting part.

Izushi: Yes, when you work within those kinds of constraints, you come up with all kinds of ideas.

Kano: Yeah, the ideas just spring up.

Iwata: When you’re making something new and there are no limits, I can’t really say it’s completely a good thing. Sometimes when there are clearly defined limits, ideas come more easily.

By the way, over a period of six years, there were 59 Game & Watch titles released, including those sold abroad. How did you come up with ideas for all of them?

Izushi: Regardless of whether they were hardware engineers, planners, or designers, everyone contributed ideas. Since so many of the games were based on everyday things, anyone could contribute good ideas.

Yamamoto: Everyone brainstormed ideas together and wrote them on a whiteboard…

Izushi: A whiteboard?

Izushi: Was it a blackboard? (laughs)

Iwata: I don’t think they had whiteboards back then. (laughs)

All (laugh)

Yamamoto: Speaking of which… (pulling out an old notebook) This is a notebook from one of those brainstorming sessions.

Iwata: Amazing! This is a precious document… This is “Chef,” isn’t it?

Izushi: You’re making fun of me! This is just an old, tattered notebook.

Yamamoto: I can do without such treasures. (laughs)

Iwata: Isn’t this your notebook, Mr. Yamamoto?

Yamamoto: It is. I wrote down the ideas we had during those brainstorming sessions. Everyone gave their opinion at those meetings. In the end, though, after everyone had spoken, it was Mr. Yokoi that made the final decisions. (laughs)

Kano: Everyone would give their opinions, we would get wrapped up in minor details, and our ideas would gradually get too complicated. At that point, Mr. Yokoi would look at what we had, point out the elements that were unnecessary, find the nucleus of what made an idea fun, and figure out how to present that core idea as an attractive, sellable product. He threw out many ideas that way.

Izushi: I hate to admit it, but that’s the truth of how it was. (laughs)

Part 3 – Building a Prototype with LED Bulbs

Iwata: Now that we’ve discussed how the ideas for the games were created, let’s discuss the next steps.

Kano: Everybody brainstormed a setting for the game, and once that was decided, Mr. Yokoi would say “I leave the rest up to you.” (laughs)

Izushi: And when he said that, it was definitely you he was leaving it up to, Mr. Kano. (laughs) We would draw up a rough draft of the game on the blackboard, and Mr. Kano would clean it up for us. At that point the game would start to look like fun, and we’d think “let’s do this!”

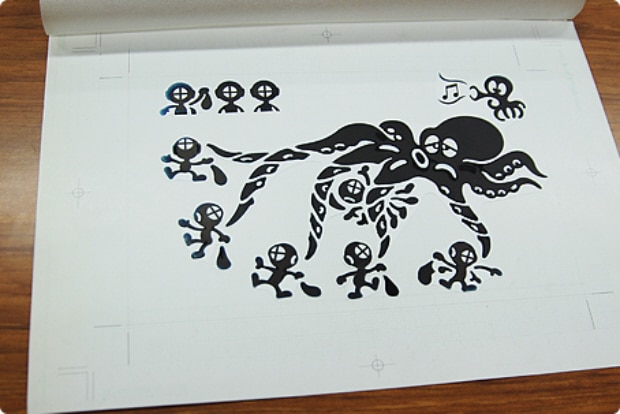

Kano: (taking out a folder) As it happens, I brought some old files, too… These are those rough drafts, the mock-ups.

Iwata: This is another amazing treasure you’ve brought out. (laughs)

Izushi: This old relic!?

Kano: These documents have all faded with age.

Izushi: This is from “Manhole.”

Iwata: And this is from “Fire.”

Yamamoto: This is from “Octopus.”

Izushi: This really takes me back…

Kano: This is the hand-drawn copy we used to build the prototypes.

Iwata: I’ve heard that those prototypes were much larger than the final Game & Watches, and lit up. How were they made?

Yamamoto: First, we would take the mock-up Mr. Kano made for us to the darkroom, and have it exposed onto film.

Iwata: You took it to a darkroom? (laughs)

Yamamoto: Yes. We’d make a negative exposure onto film.

Izushi: Then, we’d lay the film down over a 5mm-thick acrylic board, cut out the pattern with a band saw, and lay the acrylic over a blank circuit board…

Yamamoto: And then we would fill up the holes with small LED bulbs.

Iwata: Were those the same kind of LED diodes used in model-making? This all sounds like an arts and crafts class! (laughs)

Yamamoto: That’s just how it was. We had to be clever to fit all those lights in.

Kano: We used opaque acrylic, so that the light wouldn’t bleed out of the holes.

Izushi: So, rather than software programming, the work was more about cutting, gluing, and cutting out holes. It was mostly done by hand.

Iwata: It sounds like a bunch of schoolboys in shop class making a huge Game & Watch. Just how big was it?

Kano: About the same size as the paper used to make the mock-up, so A4-sized.

Iwata: So with a giant, A4-sized Game & Watch, you checked that the game was fun to play?

Yamamoto: Right, we would try it out and say things like “we should change this,” or “it’s difficult to see what’s going on here.”

Kano: It was difficult to make the movements looks natural. If it wasn’t good enough with the LED protoype…

Izushi: Yeah, we never got it right in just one try. Naturally, Mr. Yokoi’s gave us feedback. We called it the “Yokoi Standard,” and that feedback was strict.

Kano: Speaking of Game & Watch generally, out goal was to ensure that if the player made a mistake, they would think to themselves “that was my fault.”

Izushi: So their next thought would be “let me try that again!”

Yamamoto: Right, so for example, if the player felt they caught the ball, but the game registered it as a drop, they would feel that the “bzz” sound the game made was unfair.

Izushi: So we wanted to make sure that whenever the player thought they had caught the ball, the system would register it as a catch. Even if the player actually missed by a little bit, we made the system register it as a catch.

Iwata: So you put some “play” into the system.

Izushi: That’s exactly right. Our motto was “timing is everything,” so we had to rework the game and tune it many, many times. Another colourful thing about Mr. Yokoi was that he would constantly ask to make changes to improve the game. When he was trying out the prototypes, he would say things like “you’ve got the timing OK, but what about adding some kind of obstacle here?”

Kano: As far as I’m concerned, it was good to have that kind of feedback at the prototype stage, with Mr. Yokoi telling us “Hmm… let’s try again!”

Izushi: That was his catchphrase.

Kano: And at that point, he didn’t care about the staff’s opinions. We were very always reluctant to go back to the game’s mock-up…

Iwata: These are the roots of “overturning the tea-table.” (laughs)

Yamamoto: That’s right. After you think you’re done, start over…

Iwata: You had to go all the way back to the darkroom?

Yamamoto: Yes. Right back to the darkroom.

Kano: But after we tried again…

Izushi: Yeah, it turned out well.

Kano: Slowly but surely, the game would get better.

Iwata: It must have been a real pain, but to hear you talk about it, it sounds a little fun, too. (laughs)

Izushi: Everybody had a good time.

Kano: Yeah, it was great.

Iwata: How much time was there between the release of titles, back then?

Kano: Sometimes only a month.

Izushi: With Mr. Yamamoto and I taking turns writing the software, we could make a new product every month.

Iwata: That’s amazing. These days, even though games are far more complex than they were back then, with one touch of the keyboard, you can make a change and test it out. In the era of the Game & Watch, on the other hand, you had to go back to the darkroom with your hand tools. It sounds like it was a lot of work. What was the programming like?

Yamamoto: Mr. Izushi and I were rookies until the fourth title, “Fire,” but I do remember that at the beginning, the games weren’t programmed as much as they were built in hardware.

Iwata: You mean the games weren’t made by being programmed like they are now, but by building the actual hardware circuits.

Izushi: That’s right. Actually, it was the same as it was for “Racing 112” and “Block Breaker.” Keeping the gameplay in mind, you would put together a circuit schematic in your head, and pick up a soldering iron. That’s how I made the prototype for “Fire.”

Iwata: So you used a soldering iron instead of a keyboard. (laughs)

Izushi: I always thought it was faster that way. It was faster then, actually.

Yamamoto: It was, wasn’t it?

Iwata: But at some point, you changed over to conventional programming.

Izushi. Yes. When I learned to use programming languages and started to make games that way, I thought “this is so much easier!” (laughs)

Iwata: It was easer and definitely faster. (laughs)

Izushi: It was faster, and I didn’t have to get my hands dirty. (laughs)

All: (laugh)

I will update with the rest of the segments as soon as the awesome Zoc gets finished with translating the rest. Remember to stop by NeoGAF and give them so love. They also have all of the awesome pics taken from the interviews that are easily viewable there.